Detroit Art Week - Detroit, Michigan

Tyanna Buie, “Church Clothes, School Clothes, Play Clothes 3”, 2018, Hand cut screen-print, hand applied ink on paper, 25 × 27 in. Courtesy of Tyanna Buie and Simone DeSousa Gallery. [From Detroit Art Week].

“There are Black People in the Future” billboard by Alisha B. Wormsley on display in Detroit. Part of the exhibition “Manifest Destiny” curated by Ingrid LaFleur.

The second edition of Detroit Art Week was held July 17-21 – a proud five-day celebration of the city’s contemporary art. Panel talks, exhibitions, studio visits and more overlapped daily. After browsing the schedule of events, I quickly realized the unfortunate truth that I would not be able to experience all of the sights & events this year’s edition offered. Still, I experienced a sampling of the city’s contemporary artistic roster. Irregular exhibition spaces like libraries and hotel rooms, as well as outdoor sites like billboards, became exhibition venues for local artists.

I kicked off opening day with Show Me Your Shelves! an exhibition produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&), a Berlin-based art magazine focusing on African and Diasporic perspectives. Three branches of the Detroit Public Library were the venues for the exhibition, which was an artistic dialogue between black artists from Germany and the US. The exhibition will travel to Houston later this year and will, in total, feature eight artists of black and Afro-German descent.

My first library stop was an installation by Detroit artist Bree Gant at Skillman Library, a site the artist “had been interested in for a long time.” Otherlogue (2019), consisted of manufactured material – empty glass jars and an empty bottle of Hennessy – and natural matter – bees and cowries. Books lined the surrounding shelves. Recounting a fantasy narrative about Eez, a black woman folklore artist in Detroit, the piece dealt with ritual and mental health. (In “Quiet as Kept”, Gant’s essay in the special Detroit edition of C&, the artist gave another anecdote on Black spirituality and personal narrative: The essay recalls her “grandmommy’s” protective spells and the artist’s own experience in a Catholic mass – the church setting her mom attended for a “twelve-step program/ritual… not to stop drinking, but to stop sinking”).

Bree Gant, “Otherlogue”, glass jars, mussles, iron, resin, bees, cowries, 2019.

The installation occupied a semi-circular room on the upper floor of the library. The piece was staged towards the back of the room and pillars that guarded the enclave stood as guardians of the precious memories. Entering the space, I moved gingerly as not to upset the presentation and shared in the memories hidden within.

The libraries were chosen for their inherent quality as centers of knowledge production. The architecture of those spaces was a benefit to the art as well. In the third-floor atrium of another library harpist Ahya Simone, playing live alongside Frankfurt artist James Gregory Atkinson's film, “The day I stopped kissing my father”, seemingly transformed the large, empty space into a philharmonic concert hall. Elsewhere Jennifer Harge (Detroit), and Janine Jembere (Berlin) presented installations, sound and film performances reflecting their German and African American experiences.

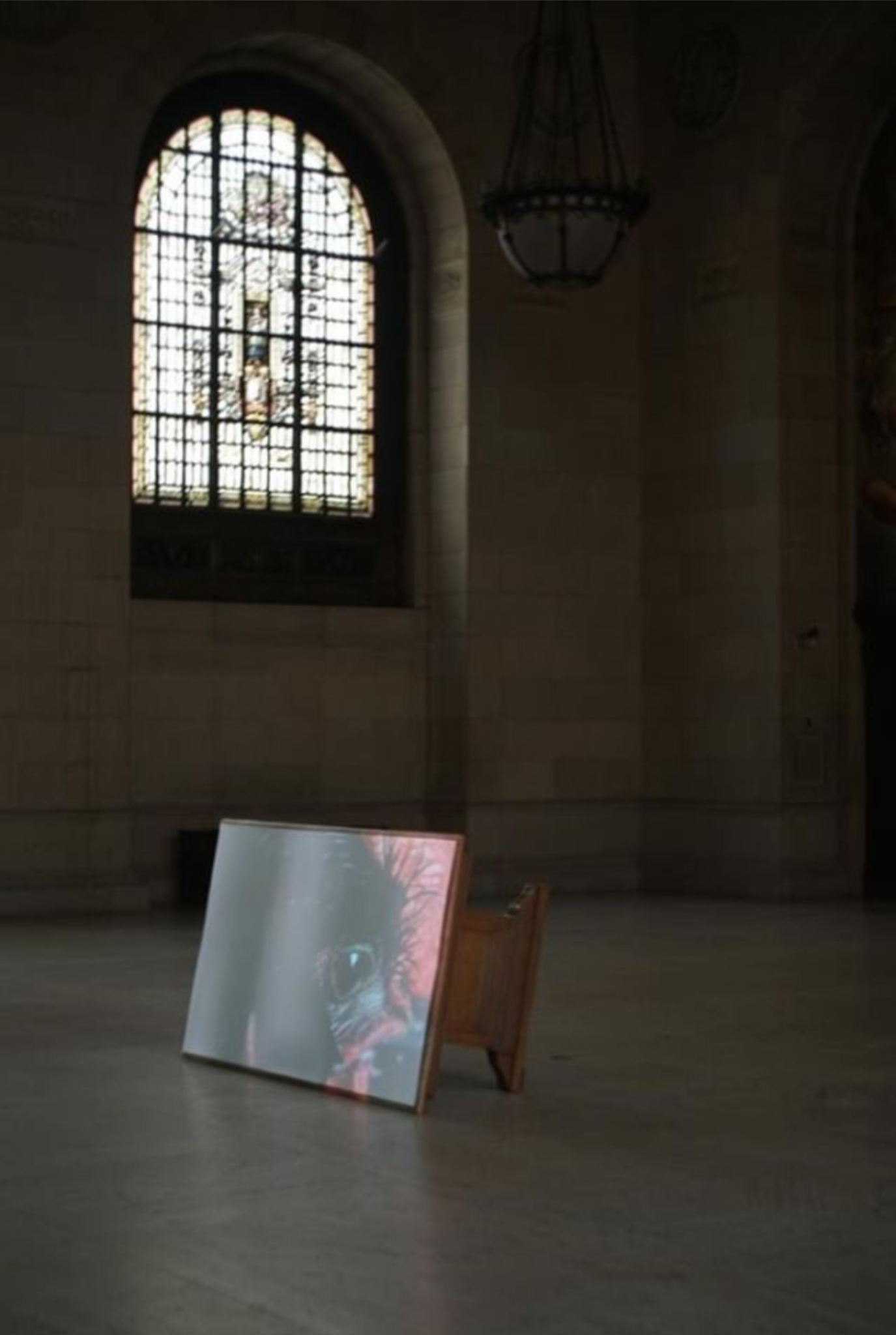

“The day I stopped kissing my father” a film by James Gregory Atkinson scored by Ahya Simone camera/edit Marcel Izquirdo Torres, 2019.

In the downtown hotel Trumbull & Porter, the exhibition “Young Curators, New Ideas V” (YCNI) transformed twelve hotel rooms into mini galleries. YCNI focused on “transformations initiated by the creative and curatorial practices of those identifying as woman, Black, POC, LGBTQ+ and gender-nonconforming.” Also common among the works was the consideration of environment, whether as a social construct – as in economy and politics – or a physical setting.

Some of my favorite mini spaces were the site-specific video installation HotBox from curator Marian Casey and artist Kameron Neal. Conceived from the queer history of Houston and more broadly, the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots, the exhibition explored queer place, legacy and erasure and remembrance. The dimmed ceiling lights inside the room allowed the rich hues of Neal’s stop-motion photographs and live videos, which played on loop from projectors, to pop. Nude imagery and even a reference to kale amplified his performance of self.

Derrick Woods-Morrow, Box of 24.

![Tyanna Buie, “Church Clothes, School Clothes, Play Clothes 3”, 2018, Hand cut screen-print, hand applied ink on paper, 25 × 27 in. Courtesy of Tyanna Buie and Simone DeSousa Gallery. [From Detroit Art Week].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/566f8e6de0327c1bbc56a3aa/1563884217647-HSJXMO1TA8MXE7SRL8RD/Tyanna+Buie+-+DAW.jpg)